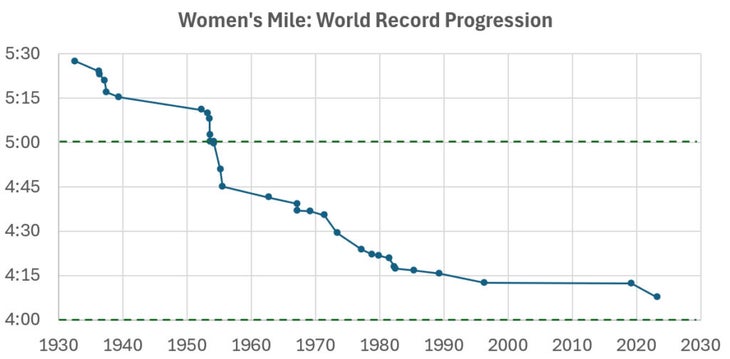

On May 29, 1954—just 23 days after Roger Bannister entered the history books as the world’s first sub-four-minute miler—a 21-year-old British woman named Diane Leather notched a similar milestone. At the Midland Counties championship meet in Birmingham, she ran 4:59.6 to become the first woman under five minutes. “Thank goodness that’s over,” she told reporters. “Now I can concentrate on my chemistry exams.”

In the seven decades since then, women have edged steadily closer to Bannister’s mark. The current world record, set by Kenya’s three-time Olympic 1,500-meter champion Faith Kipyegon in 2023, is 4:07.64. Her corresponding 1,500-meter world record of 3:49.04 is equivalent to a mile in roughly 4:06.5, according to the World Athletics scoring tables. The gap is small enough, in other words, that you might start wondering just how fast she could go, and how close to the barrier she could get, in a rule-bending exhibition race modeled after Eliud Kipchoge’s sub-two-hour marathon events.

That’s the question posed in a new study in Royal Society Open Science by University of Colorado physiologist Rodger Kram, working with colleagues Edson Soares da Silva, Wouter Hoogkamer, and Shalaya Kipp. Their conclusion: start the countdown.

The Power of Drafting

Once you start bending rules, the tricky part is deciding when to stop. A downhill sub-four mile wouldn’t be particularly interesting, for example. In their analysis, Kram et al. focus on the potential role of hyper-optimized drafting—running behind or between other runners to minimize the effects of aerodynamic drag. These same researchers have previously published research on drafting in marathoners (which I wrote about here), suggesting that getting the drafting right can save between three and five minutes for both elite and mid-pack marathoners.

Back in Bannister’s day, having pacemakers or “rabbits” leading the race and blocking the wind for you was considered controversial. The current rules permit pacemakers as long as they start at the beginning of the race. You can’t have fresh rabbits hopping in at the halfway mark, which was the key rule broken in Kipchoge’s sub-two attempts. Bannister himself was paced by his training partners for more than 80 percent of the race. Kipyegon, in contrast, was paced just past the halfway mark, and even in the first half of the race she was too far behind her pacers to get the full aerodynamic benefits of their presence. That suggests there’s still scope for improvement.

Another factor in Kipyegon’s favor is her size: she’s reported as 5’ 2”, a full foot shorter than Bannister was. You might think that air resistance should matter less to her, since she’s smaller. But smaller runners actually have to spend a greater proportion of their energy overcoming air resistance, because they have a greater ratio of surface area to volume. Kram and his colleagues calculate that when running at four-minute pace, air resistance takes 13.5 percent of Kipyegon’s energy compared to just 11.4 percent of Bannister’s. That means she has more to gain from drafting.

How Kipyegon Could Break the Four-Minute-Mile Barrier

Kipyegon ran her mile record on a windless night in Monaco. She ran her first lap of 409.3 meters in 62.60 seconds, and the subsequent 400-meter laps in 62.00, 62.20, and 60.84 seconds. She was three to four meters behind the pacers for the first lap, 2.5 meters behind in the second lap, and 2 meters behind for the beginning of the third lap before the final pacer dropped out. Optimal (but practical) drafting, the researchers suggest, has the runners about 1.2 to 1.3 meters apart.

The key question is: how much of the energy “wasted” on aerodynamic drag can you save by running close behind another runner? You can estimate this with wind tunnel experiments or computational fluid dynamics calculations, but the answers vary widely. Kram and his colleagues run the numbers with several representative values drawn from these studies.

The most conservative estimate is that you can reduce drag force by 39.5 percent at 1.3 meters behind the leader, with the savings decreasing as you drift farther back. The most optimistic one is that you can reduce it by as much as 75.6 percent with one pacer 1.2 meters ahead and a second one 1.2 meters behind you. Having a pacer behind you seems counterintuitive, but it helps keep air flowing smoothly past by minimizing the turbulence behind you.

You can use these values to estimate how fast Kipyegon would have run with exactly the same effort as her world record race but no drafting: between 4:10 and 4:12. You can also estimate what she would have run with no air resistance at all, for example on a treadmill: between 3:53 and 3:55.

And then you can plug in what she would have run with ideal pacers for the whole race. Using the more conservative 39.5 percent value for drafting effectiveness, you get a final time of 4:03.6. Using the optimistic 75.6 percent value, it’s 3:59.37—pretty much identical to Bannister’s 3:59.4 back in 1954.

Back to Mile-Record Reality?

The calculations suggests that Kipyegon could dip under four only under the most perfect conditions. But how close to perfection can we get in the real world?

For drafting, there are two basic choices: male sub-four milers who pace the entire race, or two teams of female pacers who switch off halfway. Neither would be accepted for official records, and it’s not easy finding women who can run a half-mile in under 2:00 with an even, controlled pace. The researchers point out that the last two Olympic 800-meter champions, Athing Mu and Keely Hodgkinson, are both capable of running the pace, and happen to be unusually tall, which might increase their drafting effectiveness.

In Kipchoge’s marathons, they used an arrowhead formation with six pacers (in the first attempt) and a reverse arrowhead formation with seven pacers (in second attempt, which was successful). That’s nearly impossible to implement on a track, since the arrowhead extends to the right and left of the racer—but Kram floats the idea of running at Franklin Field, the iconic home of the Penn Relays. Franklin’s lane four is 400 meters, meaning that Kipyegon could run in lane four with some of the arrowhead pacers in lanes three and five.

Kipchoge also benefited from hyper-optimized courses that minimized elevation changes and curves. You can’t make a track any flatter, but there may be ways of making it a few seconds faster. Geoff Burns, a biomechanist who works for the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, has a couple of great articles on the benefits of banked corners and springy wooden tracks. For a 400-meter track at four-minute-mile pace, Kram figures the optimal angle for banked corners would be 7 degrees around a curve with 36-meter radius.

Finally, you could take another page from Kipchoge’s playbook and push the envelope on shoe design. Current World Athletics rules limit the thickness of spikes to 20 millimeters, but Kram figures a slightly thicker midsole might unlock some extra super-spike benefits.

There’s one other wrinkle to consider. The original data on Nike’s Vaporfly supershoes—a study co-authored by Hoogkamer, Kipp, and Kram, as it happens—found that they improved running economy by four percent on average, but with individual results between 1.6 and 6.3 percent. Rumor has it that Kipchoge was on the high end of this range. Surprisingly, there seems to be a similar spread in the benefits of drafting. A study led by da Silva a few years ago found that a standardized drag force burned anywhere between 4.2 and 8.1 percent more energy in different individuals. We know that Kipyegon has once-in-a-generation running ability, but we don’t know how much she stands to benefit from drafting. A sub-four might require someone who’s off the charts in both.

All of this, of course, assumes that we believe the calculations on the benefits of drafting. The wide range of calculated values for drafting effectiveness is a sign that there’s still plenty of uncertainty about the exact numbers. Kipchoge’s sub-two marathon is generally thought to have been made possible by two key levers: supershoes and drafting. But as marathon world records have continued to fall even with suboptimal drafting, I’ve begun to think that the shoes must be a bigger factor than the drafting. There’s really only one way to find out for sure, though: we need a Breaking4 Project.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

Source link