When I started writing about sports science two decades ago, fueling advice for endurance athletes was simple. The goal was to take in roughly 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour, in order to preserve the limited supply of carbohydrate stored in your muscles and liver. More would theoretically be better, but studies had found that it simply wasn’t possible to absorb more than that from the stomach into the intestine.

The science has evolved since then, mainly with the realization that mixing different types of carbohydrate (like glucose and fructose) in specific ratios enables higher absorption rates. Current recommendations top out at 90 grams per hour, but recent studies have suggested that it’s possible to take in 120 grams per hour—and top athletes in cycling, ultra running, and other sports are reportedly going even higher than that.

In contrast to all this, a new study gave its subjects just 10 grams of carbohydrate per hour, and argues that this is all you need. This is a surprising and contrarian take, and I’m not suggesting you should swallow it whole. But it’s a good opportunity to pause the carb mania for a moment and take a closer look at the evidence and assumptions underlying the “more is better” view.

The new study is published (and free to read) in the American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology by a group of researchers at several universities led by Philip Prins and Andrew Koutnik. Its main purpose is to compare endurance performance in ten well-trained triathletes following either standard carb-heavy diets or low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets. That’s a complex and long-running debate (which I wrote about most recently in 2020) that I’m not going to get into here, other than to note that they didn’t see any significant differences either way in an endurance test lasting about 90 minutes following six weeks on either diet.

What’s more interesting here is their test of in-race carbohydrate supplementation. All the subjects did two rounds of endurance tests on each diet: one with a carb drink every 20 minutes totaling 10 grams of carbs per hour, the other with a placebo drink with no carbs. On average, the athletes lasted 22 percent longer with the carb drink, regardless of which diet they were on. That’s a big improvement. Time-to-exhaustion tests, where you hang on as long as possible at a predetermined pace, are different than races, but an improvement like that likely corresponds to going one to two percent faster in a race.

The reason they chose such a small dose of carbohydrates is that one of the study authors, South African scientist Tim Noakes, now believes that we’ve badly misunderstood the role of in-race carbohydrates. The traditional view is that we drink carbs to prevent our muscles from running out of glycogen, the form in which muscles store carbs. Noakes’s view is that glycogen doesn’t matter, and that the real benefit is preventing a blood sugar crash. This is a brain-centered view of endurance: keeping blood sugar high convinces the brain that everything is OK, so the muscles—which were never truly in danger of running out of carbs—keep on pumping.

If blood sugar is what matters, then we don’t need to choke down such large quantities of carbohydrate after all: at any given moment, there’s only about a teaspoon of glucose circulating in your bloodstream. What’s missing from Prins and Koutnik’s study is an explicit test of higher carb doses. We see that 10 grams per hour helps, whether by maintaining blood sugar or simply by tricking the brain into thinking that fuel is coming (as has been demonstrated with studies of swishing sports drink in the mouth then spitting it out). But we don’t know whether, say, 30 grams per hour would have been better or worse.

On the other hand, you might imagine that the conventional view of carbohydrate needs—the more the better—is backed by plenty of evidence. And you’d be right. But Noakes argues that in all the studies showing that the depletion of muscle glycogen corresponds to a drop-off in performance, the subjects also had low blood sugar. We’ve been watching the wrong variable, in his view, and drawn the wrong conclusions. This argument echoes Noakes’s critique of hydration research, which was that studies didn’t distinguish between being dehydrated and feeling thirsty. In his view, being dehydrated only matters if you feel thirsty, since it’s your brain that decides when to slow down.

The debate gets pretty complicated at this point, with dueling interpretations of the minute details of decades of research. Rather than getting lost in the physiology, though, I think the simplest test is to ask about the outcome we really care about: Does taking higher loads of carbohydrate lead to better performance? When you dig into this dose-response literature, the findings aren’t as clear as I might have expected.

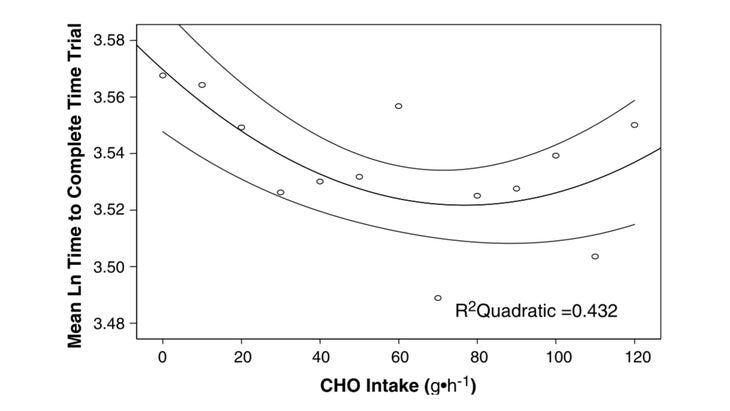

Here’s a graph from one of the key papers, a 2013 study from the Gatorade Sports Science Institute (who, I’m sure I don’t need to point out, like the idea that more carbs are better). Fifty-one cyclists and triathletes completed a series of tests consisting of two hours of moderately hard cycling followed by a 20-kilometer all-out time trial, while consuming anywhere from 0 to 120 grams of carbohydrate per hour, in 10-gram increments. The results:

The paper describes this relationship as a “curvilinear dose-response relationship”: more carbs are better initially, but at the highest doses more carbs hurt performance. The sweet spot where performance is optimized, in this data, is 78 grams of carbohydrate per hour, consistent with the idea that 60 to 90 grams is the right range.

But take another look at that data. Performance is worst at 0 or 10 grams; it’s a little better at 20 grams. Take those three data points out, and it’s hard to see any evidence of a dose-response relationship above 30 grams. It’s certainly not a very strong demonstration that 60 grams is better than 30 grams, let alone that there are benefits from upping to 90 or 120 grams.

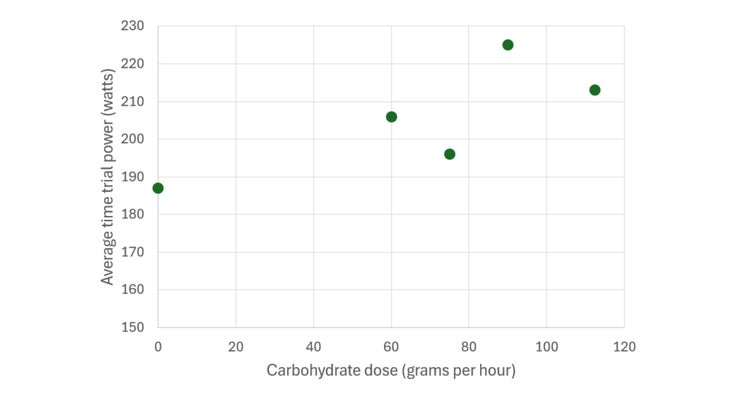

The case for 90 grams over 60 grams, using a more modern mix of carbohydrates, is made in this 2018 study from researchers at Leeds Beckett University. Ten subjects tested 0, 60, 75, 90, and 112.5 grams of carbohydrate per hour for two hours of cycling followed by a 30-minute time trial. Here’s the average power outputs in the time trial:

From this, you might conclude that 90 grams is indeed the best bet. It’s hardly definitive, though. The placebo option, with no carbs at all, is clearly the worst option, but it’s not that far from the 75-gram result, and there’s no data to compare with for lower doses. How would the cyclists have fared with, say, 20 grams an hour—enough, as Noakes would argue, to keep blood sugar constant but not to conserve muscle glycogen in the legs?

Personally, I find it hard to believe that muscle glycogen doesn’t matter. Even if we don’t grind to a halt because our glycogen tanks are empty, there’s evidence that we begin slowing down when our muscles are partly depleted. It could even be that the brain monitors glycogen levels and dials back performance as fuel levels drop, just as Noakes proposes for blood sugar.

Whether that means big carb doses like 120 grams per hour are a good idea is a different question, though. The scientific data that I posted above doesn’t seem overwhelmingly convincing. The real-world experiences of elite athletes are much more compelling, and that evidence should be taken seriously. I’d love to see better dose-response data showing more clearly what happens across the whole range of intakes between 0 and 120 grams per hour. But those are hard studies to do, so in the meantime we’re stuck with the golden rule of training and sports science: try a few different approaches, and see what works best for you.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

Source link