Everyone has a plan, Mike Tyson famously said, until they get punched in the face. The endurance athlete’s version of that dictum might be: everyone has a great VO2 max and an efficient running stride until they’ve run 20 miles. How you fare in those final miles depends, in large part, on how steeply these factors have declined over the course of the race.

This is the fundamental premise of “fatigue resistance,” an idea I first wrote about back in 2021 that is currently one of the hottest topics in endurance science. The old view was that you could run some lab tests to determine an athlete’s VO2 max, lactate threshold, and running economy (or an equivalent measure of efficiency for other sports) and calculate their predicted finishing time. The new insight is that these factors change as you fatigue—and crucially, they change more in some people than others. Having good fatigue resistance, then, is the ”fourth dimension” of endurance.

So far, most of the research on fatigue resistance—which is also called “durability” or “physiological resilience”—has focused on demonstrating that it plays a role in determining who wins races. What we really want to know, of course, is how to improve it. That’s the question a pair of new papers tackles.

The Case for Strength Training

The first study, published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise by Michele Zanini and his colleagues at Loughborough University in Britain, tests a twice-a-week strength training program in 28 well-trained runners with an average 10K best of 39 minutes. Half of them added the strength routine to their usual training for ten weeks, while the other half just carried on with their usual training.

The performance test was a 90-minute run at a pace near lactate threshold, followed by an all-out time-to-exhaustion test that lasted about five minutes. Every 15 minutes during the 90-minute run, they measured running economy, which quantifies how much energy you burn to sustain a given pace. They expected running economy to get worse as the runners fatigued, but wanted to find out whether strength training could counteract this deterioration.

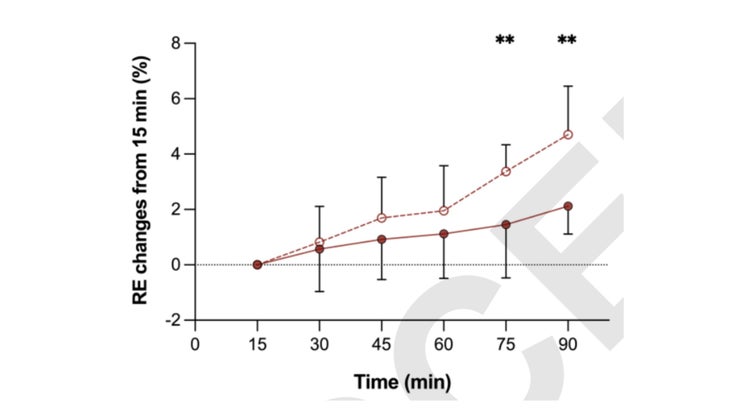

The results were encouraging. Before strength training, running economy got 4.7 percent worse after 90 minutes of running; after strength training, it only declined by 2.1 percent over the same period of time. Here’s how running economy changed over the course of the run, with white circles showing the baseline test and black circles showing the post-strength-training test:

Note that a positive change (i.e. the line drifting upward) means that the runners were burning more energy to maintain the same pace as time went on. In the baseline test, running economy starts getting significantly worse after about an hour. After strength training, this drift is less pronounced.

The strength training program in the study consisted of a mix of heavy weights and explosive plyometrics. The resistance exercises were the back squat, single-leg press, and seated isometric calf raises, typically with around three sets of six reps. The plyometrics included vertical exercises (pogo jumps and drop jumps) and horizontal exercises (hops and bounding). It’s not clear from this study whether the heavy weights or the plyometrics provided the magic, though Zanini points out that both methods have produced similar results in previous studies of strength training and running economy.

Why does strength training improve fatigue resistance? Here we’re limited to speculation. It may have something to do with making fast-twitch muscle fibers more efficient, or making tendons stiffer and springer, or improving strength sufficiently to maintain good running form for longer.

Other Options for Boosting Fatigue Resistance

The other new paper is published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports by Andy Jones of the University of Exeter in Britain and Brett Kirby of the Nike Sport Research Lab. Jones and Kirby played key roles in Nike’s Breaking2 Project in 2017, where they encountered what you might call the Zersenay Tadese Problem. Tadese had exceptional lab values, including the best running economy ever measured, but repeatedly struggled at the marathon distance, while his teammate Eliud Kipchoge had relatively modest lab values but turned out to be the dominant marathon runner of the decade. The difference, presumably, was that Kipchoge had better fatigue resistance.

The new paper sums up their thoughts on fatigue resistance, including some speculation on how to improve it. Strength training, they note, is one option—though they point out that few of the East African runners who currently dominate international marathoning do structured strength training.

Overall, their view seems to be that the best ways of improving fatigue resistance are mostly the things that endurance athletes already do to get better: high mileage, especially accumulated over many years; long runs, including some sections at close to race pace; intense interval sessions; following a pyramidal training distribution. There may also be some more subtle effects from, for example, doing some fasted training or living at high altitude. None of these are uniquely targeted at fatigue resistance.

Jones and Kirby do mention one other possibility: put on some supershoes. There’s likely an instant effect, since the heavy cushioning reduces muscle damage and enables you to keep striding smoothly through the later stages of a marathon. And there may also be a chronic effect: the cushioning allows you to absorb and recover from higher levels of training, enabling you to safely rack up higher mileage and thus improving your fatigue resistance over time.

The overall impression, then, is more evolution than revolution. All these years, we’ve been training to maximize VO2 max, running economy, and threshold. Now we’ve got a new target—fatigue resistance—but so far the best ways of improving seem to be mostly the things we’re already doing. Even Zanini’s strength-training routine is the kind of thing coaches and scientists already recommend. But if you have the sense that fatigue resistance is one of your weaknesses, you now have extra motivation to move strength training and plyometrics from the “I should do this” column to “I’m doing it.”

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

Source link