Consider this age-old dilemma: you’re at the bottom of a hill, and you want to get to the top. Should you head straight up the steepest slope or switchback back and forth at a gentler incline? The answer depends on the context. If you’re on a marked trail, for example, you should definitely stick to the prescribed switchbacks. But a more general answer involves digging into the physics.

That’s the goal of a new study in the journal Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, from a research team led by David Looney and Adam Potter of the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. Previous researchers have found that “steeper is cheaper” for runners, meaning that it takes less energy to ascend directly up steeper slopes. But it wasn’t clear whether the same is true for walkers and backpackers, or whether the answers change depending on how hot or cold it is.

The Best Slope for Trail Runners

For starters, it’s worth looking back at the trail-running data. In 2016, researchers at the University of Colorado decided to study the increasingly popular world of vertical kilometer races. The total elevation gain in these races is set at 1,000 meters, or 3,281 feet, but every course is different. A steep slope will have a shorter course distance but be harder to run up. A gentle slope will be easier to run up but cover a longer total distance. For a given finishing time, what’s the sweet spot?

The Colorado researchers built the world’s steepest treadmill (video here), capable of reaching a slope of 45 degrees—a 100-percent grade, in other words. To put that into perspective, a black diamond ski run is typically about 25 degrees, and gym treadmills rarely go more than 9 degrees. They had to line the treadmill belt with sandpaper for grip, and even then runners couldn’t stay balanced beyond 40 degrees.

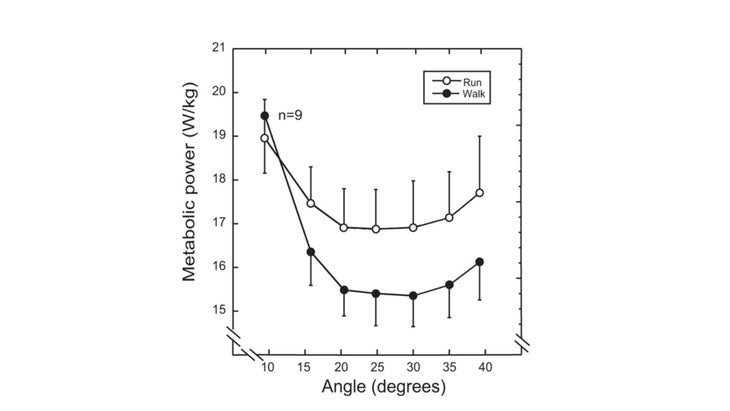

They tested runners at a variety of slopes, with the treadmill speed adjusted so that they were always gaining elevation at the same rate, equivalent to a vertical kilometer in a very respectable time of 48 minutes (the world record is just under 30 minutes). Here’s what the results looked like for walking (black circles) and running (white circles), with metabolic rate (basically how quickly they were burning calories) on the vertical axis:

At gentle slopes like 10 degrees, it takes a lot of energy to climb, because the treadmill is moving really fast to gain the required elevation. At steeper slopes, the calorie burn decreases: steeper is indeed cheaper, at least up to a point. Beyond about 30 degrees, calorie burn starts increasing again, presumably because the incline is now so steep that it’s hard climb efficiently. The sweet spot, then, is between 20 and 30 degrees—which, as it turns out, corresponds to the average slopes of the courses where the fast vertical kilometers are held.

(You might also notice that walking burns less energy than running for most of the steeper slopes. That’s a truth that most mountain and trail runners eventually discover for themselves. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you should only walk up hills, as I explored in this article on the walk/run dilemma in trail running.)

The Best Slope for Hikers

Climbing a kilometer in 48 minutes is really fast, the aerobic equivalent of running as hard as you can for 10 kilometers, so it’s not clear that the Colorado results have much relevance for backpackers or military personnel. Looney and his colleagues decided to run similar experiments at a range of much slower climbing speeds. The Colorado study had a climbing rate of 21 vertical meters per minute; Looney’s study looks at four different climbing rates of between 1.9 and 7.8 meters per minute, a much more realistic range for hikers.

The overall results are similar to the running results: steeper was once again cheaper. For each climbing rate, choosing a steeper slope corresponded to burning fewer calories. As with the running data, there’s probably a point where getting too steep becomes counterproductive. But the steepest slope in Looney’s study was only about 13 degrees, and in that range steeper was always better.

There was an additional wrinkle in Looney’s protocol: the military is increasingly focused on Arctic operations, so they ran the same protocol at three different temperatures: 32, 50, and 68 degrees Fahrenheit. The two warmer temperatures were basically the same, but the data at 32 degrees was slightly different.

At slower vertical climbing rates, calorie burn rates were higher than normal at 32 degrees, because the subjects were spending extra energy keeping themselves warm by shivering and activating their brown fat. At higher vertical climbing rates, calorie burn rates were roughly the same regardless of temperature, presumably because they were working hard enough to stay warm even at 32 degrees. In cold temperatures, in other words, pushing harder can sometimes be more efficient because it saves you the energetic cost of keeping yourself warm. (Conversely, you might imagine that the steepest slopes would cause problems in really hot conditions because you’re more likely to overheat.)

The Takeaway

The most important caveat to keep in mind when interpreting these results is that the comparisons are based on a fixed climbing rate. If you’re at the bottom of a hill and want to get to the top in a given amount of time, then choosing a steeper route will generally save you energy. If you’ve got all the time in the world and don’t care how long it takes you to reach the summit, then you might well choose to take a gentler route that will feel easier as you climb.

Most of us, though, live in a world where time is scarce. Even if we’re not racing vertical kilometers, we’re hoping to make it to the summit and back, or to the next campsite, before dark. In that situation, if you’re choosing between two routes, remember this: If one route is twice as steep as the other, you’d have to walk twice as fast up the gentler route to reach the top in the same time. Counterintuitive though it may sound, that data shows that under most circumstances, twice as steep is easier than twice as fast.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

Source link