Back in 2015, a trio of scientists led by the University of Michigan’s Sandra Hunter, one of the world’s leading experts on male-female performance differences, wrote a paper in the Journal of Applied Physiology titled “The Two-Hour Marathon: What’s the Equivalent for Women?” The comparable barrier, they concluded, had already been broken by Paula Radcliffe’s 2003 world record of 2:15:25.

Since 2015, the men’s record has dropped by 1.9 percent to 2:00:35 (with Eliud Kipchoge also notching an unofficial 1:59:41 in a record-ineligible exhibition race). The women’s record, after Ruth Chepngetich’s Chicago Marathon win earlier this month, has now dropped by a dizzying 4.0 percent to 2:09:56. The claim that Radcliffe had run the equivalent of sub-2:00 was debatable; the claim that Chepngetich has done so is not. This is the greatest marathon performance in history by virtually all metrics—and it has stirred up a hornet’s nest of reactions.

To be a fan of endurance sports in the modern era is to live with a baseline level of skepticism. We know that top athletes sometimes dope, because they’re sometimes caught. We also know that those who set records are, by definition, faster than these confirmed dopers. But Chepngetich’s world marathon record sparked a bigger backlash than anything we’ve previously seen. Politicians in Kenya’s parliament demanded an apology after Letsrun’s Robert Johnson asked Chepngetich a leading question—“Some people may think that the time is too fast and you must be doping. What would you say to them?”—at the post-race press conference. Former Boston Marathon champion and longtime running journalist Amby Burfoot made his suspicions clear: “We don’t have proof,” he wrote in an opinion piece, “but we know what we know.”

How is it possible that a woman could run five minutes faster than what was recently thought to be the equivalent of a men’s sub-two-hour marathon? Is it possible? These are questions that we can’t answer definitively, but there are some clues in the scientific literature that are worth bearing in mind as we consider what this new era means. Here are three points I’ve been mulling over the past week:

Maybe the Shoes Give Women an Edge

We know that supershoes have led to a wholesale rewriting of road racing records since 2016. But why is it that women seem to be improving more rapidly than men? As we’ve seen, women gained more than twice as much as men in the marathon since 2016. The same is true at other distances: the women’s 10K record has improved by 5.4 percent, and the half-marathon record by 3.5 percent; the men have improved by 1.2 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively.

There are a few possible explanations. One is sociocultural: East African men have been dominating international running for decades, but women from the region have emerged more recently, so the talent pool may still be deepening. Or perhaps, as with the Eastern Bloc women on anabolic steroids in the 1980s, there’s an as-yet-undetected form of doping that helps women more than men.

Another possibility, raised in a recent journal article in Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, is that women get a bigger boost from supershoes. A team of researchers led by Joel Mason of Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany, proposes several hypotheses for why the shoes might work better for women.

One theory is that, even though male athletes tend to be taller and heavier than female athletes, the maximum midsole thickness of 40 millimetres (about 1.6 inches) imposed by World Athletics is the same for everyone. That means women’s effective leg length gets a bigger proportional increase, and their shoes are thicker relative to length. Women’s lighter weight is also less likely to make the midsole “bottom out” when it’s compressed. If the maximum midsole thickness was proportional to shoe size, this theory suggests, the differences between men and women would shrink or disappear.

There are also more esoteric theories, like sex differences in the elastic properties of muscles and tendons that enhance the female response to the shoes. And there’s the simple fact that women, with shorter legs, take more steps than men, which “may simply provide more opportunity for the supershoe mechanisms to interact with the ground, potentially compounding the benefits.”

All these mechanisms are speculative, but the performance data showing that women are improving more rapidly than men is quite clear (and has shown up in other recent studies too). This makes Chepngetich’s sub-2:10 a little more palatable—but it doesn’t explain why she’s so far ahead of all the other women who should presumably be getting similar benefits. The previous record, set last year, was 2:11:53; the next best time after that is 2:13:44. That’s a gap of three minutes and 48 seconds to the third best time in history. For comparison, 49 different men have run within 3:48 of the men’s world record.

There’s Something in the Air

When I was covering Nike’s Breaking2 project in 2017, they deployed a vast array of scientific tweaks to aid Eliud Kipchoge and his peers in their quest for a sub-two: high-tech training analysis, newly designed race suits, wearable oxygen sensors, and so on. After sifting through the details, my impression was that only two interventions had the potential to really move the needle: supershoes and drafting.

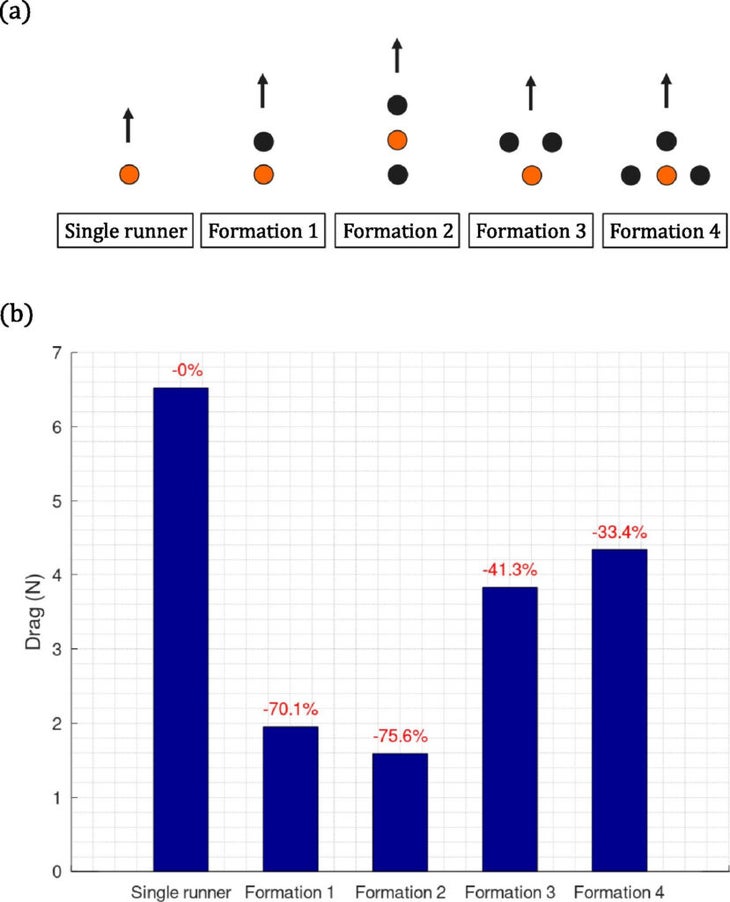

There’s a lot of debate about how much drafting really matters at marathon speeds (unlike cycling speeds, where it’s clearly a huge factor). One theoretical analysis from 2022 concluded that the seven-person arrow formation that Kipchoge used in his sub-two run saved 5:29 compared to running solo. That’s a surprisingly big number, and when you consider that Kelvin Kiptum hardly drafted at all in his marathon world record last year, it becomes hard to swallow.

Chepngetich had two male pacemakers who guided her for almost the entire race. I believe that this sort of pacing help has big mental benefits, in the same way that pacing lights have helped spur faster times on the track. But as University of Colorado biomechanist Rodger Kram pointed out in an email after the race, it was notable that Chepngetich ran behind and between her pacers, rather than directly behind either of them.

There’s a 2022 study that compared this drafting configuration to several others. Chepngetich’s formation theoretically saved 1.6 minutes compared to running alone. Running in a pace line, with one pacer directly in front and the other directly behind, would have saved 2.6 minutes. Here’s the data showing calculated drag forces for various configurations:

The implication here is that Chepngetich’s performance wasn’t the result of everything coming together absolutely perfectly. On the contrary, she could have gone faster! Her pacing suggests the same thing: she ran the first half in 1:04:16 then slowed in the second half to 1:05:40, which scientists believe is not the best way to run your fastest possible time.

So She’s Doping?

The female supershoe advantage offers a plausible explanation for how Chepngetich’s record could be so much better than Kiptum’s. Notably, according to Jonathan Gault’s excellent account of the new record, Chepngetich raced in Nike’s new Alphafly 3 shoe, a switch from the Vaporfly she had worn in previous years. She also began using Maurten’s hydrogel carbohydrate drink for the first time. With a little work, you can construct a case for how, at the age of 30, Chepngetich is suddenly so much better than she was before.

Is this merely an exercise in fantasy? After all, Chepngetich’s agent, Federico Rosa, has overseen the careers of several high-profile marathoners who were caught using drugs, including multi-time Boston and Chicago marathon champion Rito Jeptoo and 2016 Olympic champion Jemima Sumgong.

Like many running fans, I’ve been wrestling with the doping question for the past week. And I’ve found myself thinking about the seemingly unrelated problem of injury prediction. Say you test thousands of soccer players for hamstring strength, follow them for a few years, and find that those with weaker hamstrings are more likely to get injured. Eureka! Now you know that players with weaker hamstrings should do extra strengthening exercises.

But there’s one problem: how do you set the threshold for what constitutes “weak” hamstrings? If you set it too high, you’ll have a lot of false negatives, meaning that players who should have strengthened their hamstrings didn’t. If you set it too low, you’ll have a lot of false positives, meaning that players who didn’t need to strengthen their hamstrings wasted time on hamstring exercises.

What researchers have concluded over the years is that it’s virtually impossible to set a threshold that keeps both false negatives and false positives to an acceptable level. Even when you have good data associating a risk factor (hamstring strength) with an outcome (injury), in practice you can’t tell who’s at risk. If you think hamstring strengthening reduces injury risk and is worth the time and energy required, you should tell all your players to do it.

I feel the same way when friends ask whether I think Chepngetich is doping. There is, in fact, good evidence that sudden jumps in performance can be a clue about doping, an approach called “performance profiling.” But it doesn’t tell you if someone is cheating; it merely flags that you should target that person for testing. Chepngetich’s performance raises a number of red flags: the time itself; her massive improvement at the age of 30; her association with Rosa; the fact that Kenya currently has 106 track and field athletes suspended by the Athletics Integrity Unit.

But where, exactly, is the threshold of red flags that tells us she’s doping? It’s simply not possible to set one that doesn’t catch innocent athletes in its net. Unlike the most skeptical running fans, I don’t believe that all elite athletes are doping. I know several Olympic finalists who I’m confident weren’t doping—though, by the same token, I can never be 100 percent sure they weren’t. As with the need for hamstring exercises to prevent injury, I simply have to assume that doping is a possibility, but not a certainty, for everyone.

There’s one final detail worth noting. Chepngetich’s first-half split of 1:04:16 was crazy, but it wasn’t totally unprecedented. Last year in Chicago, she went out in 1:05:42; the year before that, she split 1:05:44. In those previous races, she faded badly in the second half, but she clearly believed she was capable of running close to 2:10 even then. A breakthrough like this only happens when someone believes it’s possible—and now that Chepngetich has done it, others will be trying to follow.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link