Popular interest in living longer is hardly new, but it spiked in the past few years. Reasons for this aren’t exactly clear. The pandemic reminding us of our mortality? A growing number of Boomers looking to redline their retirements?

Our fixation on longevity is rising at the same time that our health appears to be sinking. A 2018 study from researchers at the University of North Carolina made waves by concluding that only 12 percent of Americans are metabolically healthy. What’s more, according to data from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, average life expectancy fell between 2019 and 2021, the biggest decline since the early 20th century. Granted, that statistic was affected by COVID-19, but chronic disease played a significant role as well.

The renewed obsession with healthier living has given rise to some longevity-oriented products and services, many with a fitness slant. No doubt the success of Outlive helped prime the market. Equinox, the upscale fitness chain, recently launched a $40,000-a-year wellness and longevity package called Optimize, which includes blood analysis, a personal trainer, and individualized sleep coaching.

In New York City, a startup called Continuum goes one better: for $10,000 per month, you get a precision health plan crafted by AI, a full biometric analysis, massages, nutrient-rich IV drips, and other luxe benefits, laid out in a swanky 25,000-square-foot private gym in Greenwich Village.

I had a hard time reconciling the new longevity bling—and the hefty price tags—with the lives of actual people living to be 90 or 100. I doubted that most of them had ever heard of VO2 max or set foot in a weight room. Maybe they were all just genetic-lottery winners?

I reached out to Dan Buettner, the author of Blue Zones, the bestselling book turned Netflix series that takes a close look at five places in the world where people live the longest. Buettner is a journalist, not a doctor or scientist, but he’d spent ample time with centenarians. He said that he liked Outlive and thought the science was sound, but he was skeptical because following its advice already “requires a person who is two or three standard deviations from the norm when it comes to discipline, income, and presence of mind.”

Attia arrived in the longevity field via a circuitous path. He grew up in Toronto, the son of Egyptian parents who immigrated to Canada. In Outlive he reveals that, as a child, he was physically and sexually abused—he doesn’t say by who, just that it wasn’t a family member. As a teenager he took up boxing, which helped him cope with the trauma. “I got to punch bags, and people, and that channeled my anger,” he writes. Despite this and other outlets, emotional problems followed him into adulthood.

His past helped set him on a course toward medicine. As an undergraduate at Queen’s University at Kingston, in Ontario, he volunteered at a shelter for abused kids. He attended medical school at Stanford University, and then did a prestigious surgical residency at Johns Hopkins before dropping out in his fifth year. Something wasn’t quite working for him in that world. To Attia, traditional medicine seemed entrenched, resistant to new approaches and new ways of thinking. He believed that there had to be a better way.

Attia believes that you can prevent decline through an aggressive combination of exercise, lifestyle, and elements from personalized health care, or what he calls Medicine 3.0. Can getting old suck less? He says that the answer is a resounding yes.

After bailing from medicine altogether, he took a job with McKinsey and Company, the global management-consulting giant based in New York City. He had a strong penchant for mathematics, which played well at McKinsey, where Attia developed a system of thinking involving frameworks, risk, and probability that would eventually become the foundation of his approach to Medicine 3.0.

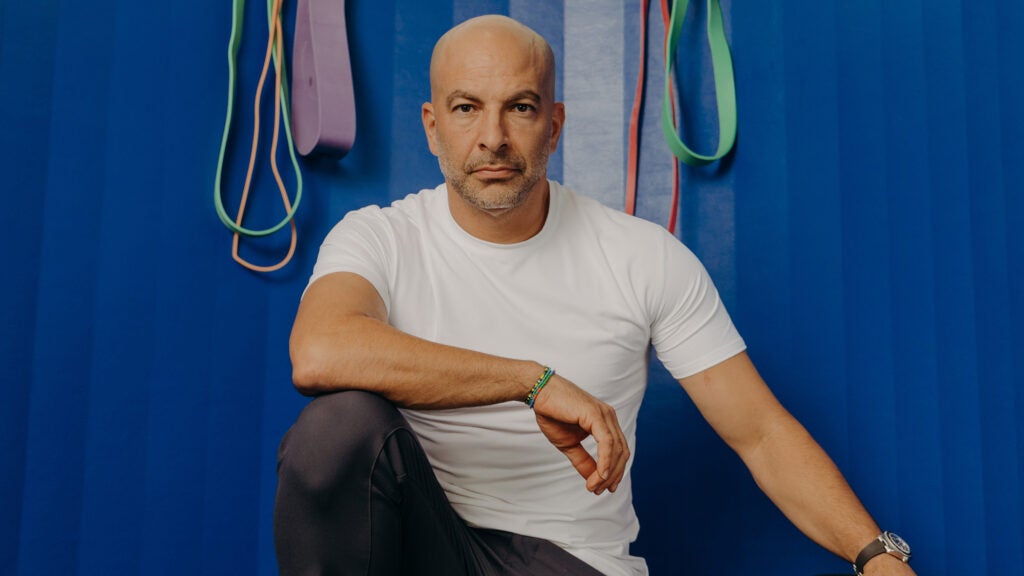

Attia was also a serious amateur athlete who pushed his own fitness to the edge. In boxing he competed at an elite junior level. As an adult, he transitioned into endurance sports, throwing himself into cycling and swimming. Among other impressive feats, in 2005 he swam from Catalina Island to Los Angeles—about 20 miles in 10 hours and 34 minutes. More recently, he’s focused on rucking, which involves strenuous hiking with a weighted backpack—in his case, often 50 pounds or more.

He also started moving back toward medicine, this time in private practice. Around 2014, he wrote down his manifesto about health, ideas that would eventually grow into Outlive. The key to a longer life, he realized, was keeping chronic disease at bay. Nothing accomplishes this better than exercise, Attia argues.

This wasn’t merely an overzealous proclamation from a man obsessed with his own fitness. Scientific literature showed clearly how effective exercise could be in preventing, and even treating, chronic disease. Such thinking started to become popular in the modern era thanks in part to books such as W. E. Harris’s Jogging (1966) and Kenneth Cooper’s Aerobics (1968), which helped connect the dots between fitness and health, and is sometimes credited with helping launch the running boom of the 1970s.

The data was so convincing that, in 2007, the American College of Sports Medicine joined forces with the American Medical Association to launch Exercise Is Medicine, a trademarked initiative to help facilitate the adoption of fitness metrics among medical professionals. Doctors, they urged, shouldn’t just check your blood pressure. They should track how much physical activity you get every day.

“There is no chronic disease that exercise doesn’t touch,” says Robert Sallis, a clinical professor of family medicine in Fontana, California, and founder of Exercise Is Medicine. “It makes so much sense that this ought to be a first-line prescription.”

Though they’re great in theory, attempts to rely on fitness as either prevention or therapy haven’t worked well in practice, Sallis says. Busy physicians rarely have time to talk to patients about their diet and physical activity, and if they do the conversation is often brief and vague. “It’s frustrating,” says Sallis. “It’s all about pills and procedures. We’re not putting ads on TV saying, ‘Ask your doctor about exercise.’ ”

My conversation with Sallis reminds me that so much about exercise doesn’t mix well with contemporary culture. We’ve engineered most movement out of our lives; we eat too much, drink too much, stress too much, and sleep too little. For many exercise is arduous and unpleasant, and it has to be stacked on top of other demands, like working a job (or jobs), raising a family, and managing the relentless addictions and distractions of late capitalism.

If that doesn’t make things hard enough, we also aren’t particularly well adapted to exercise, argues evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman, author of Exercised: The Science of Physical Activity, Rest, and Health. Viewed through a Darwinian lens, being lazy—that is, conserving energy—is a survival tactic. According to Lieberman, exercise is a “weird” modern contrivance invented to replace eons of physical effort.

As has been true for most of human evolution, exercise—physical activity—must be “necessary” and “fun” to be sustainable, Lieberman writes. Absent those qualities, we’re swimming against an increasingly swift current, if not already being washed downstream.

Source link